Hi again there, hi hi. Kendra, here, the co-founder and past Artistic Director of The Only Animal, and you might know that I left the company and Canada in July of this year. For me, The Only Animal was about making theatre in deep relationship with place and the natural world. As a site-specific theatre maker, my relationship with theatre and the land have always been deeply entwined. The new AD, who you now know, Barbara Adler, kindly commissioned a series of letters that would document the year ahead—a year where I might fall in love with a new landscape. Originally, this was imagined as letters written one AD to another. But as I was writing, I found that while I invested much time in the AD transition, I had neglected another transition entirely—with The Only Animal itself, that great, lumbering, beast who I lived with for 18 years. I want to preface this by saying that I did choose to leave, I can tell you that it was for Important Reasons, what my family needed, a choice made with Love. I do not regret it, but, spoiler alert, it’s been tough. I wrote this first letter and showed it to my partner who said it was 25% too sad. I edited it and showed it to Colin, who said it was still 10% too sad. I tried. Reader, you will have to do the rest of the editing yourself, okay? Bleep right over any bits you wish, there are funny bits too! Weird bits! Anyway, here is a little of my journey since I left, as told to The Only Animal.

Dear Animal,

The dawn is breaking as I am writing this letter. This will not surprise you. I used to set my alarm for 3am so that we could spend a few hours together, you and me, before the kids awoke. There, as the sun came up, it was the black turning to a hundred shades of green. Here, it is a smudge of orange and red pushed up by mountains. As a little kid I drew sky as a line at the top of the paper and the art teacher got right down to my level, and said, ‘Look outside, Kendra, do you see that the sky comes all the way down to the ground?’ I was dumbfounded because it did. Living in the mountains isn’t like that. Here the rock is everywhere pushing at the sky, in an enormous struggle. It is not like living at sea level. It is not like home.

As I finish that paragraph, I look up again. Now, the sky is purple with yellow coming. Things change. Boy, do they change.

And change is the engine of theatre, and you, my big, bright, Animal, you might love it here. This is a place of drama. And this matters, because as you know, landscape is everything to me, although plants rank high and animals probably tie. (I struggle with my own species. Later, I’ll tell you what my therapist says about that. )

But first, we have to begin and we have to begin somewhere, and I’m here, in Sunshine, Colorado, the ancestral homelands of Núu-agha-tʉvʉ-pʉ̱ and Hinono’eino Nations. It is 1473 miles away from you–I am not sure how to do the conversion but that is approximately sixhundredmillionkilometres. Give or take.

I’m writing today, but all day yesterday I was sick with some weird thing that made my insides ache from my pubic bone to my breastbone. I told my kids I was possessed by demons. But, when it worsened, I consider I might have Cancer of the Everything. Later still, my worst fears are confirmed; I am pregnant with aliens.

Remember last year, when we were doing an Artist Brigade field trip to Gambier Island and we went to scout with a nature educator named Tim. He knew a lot of beautiful things and took us in his motorboat. Bouncing across Howe Sound, he tells us ‘islands are mountain tops of another era’. Man, I loved that. (I fed you that tidbit, Animal, how delicious. You know how a morsel like that can grow into a world. We have made a lot of worlds together, you and I.)

Now, here, on a mountain top at 7100 feet, I’m patient, but the ocean doesn’t come. I pick my kid up from school. He has his sweatshirt on, not inside-out, but upside-down.

It’s been a day. A week. Seven weeks now, when are we going home?

So far, 484 words in, I am not yet in relationship with place. It seems impossible. Count your blessings, Kendra. I count: 26 letters of the alphabet, 16oz of coffee, and 83% battery power. What can we do here?

At home, it is very barely possible to pick enough thimbleberries in their brief season to make 125ml of thimbleberry jam. It is delightful at times to do an impossible thing. You know that too, of course.

All the same, I didn’t pick berries this year before I left. I just watched them. Everything was too perfect. I just want it to stay, just there, exactly like it was.

In my Colorado bed, I dream that I am adrift in a submersible that lands with a thud on the bottom of the ocean. My cabin mates and I decided that we should open the door, and let the ocean rush in, and then we could swim and try to make it to the surface. In the dream, I speak to myself very firmly. BRACE YOURSELF, FANCONI, GRAB ON TO WHATEVER YOU CAN. Then, I woke up. Kinda.

All day, I gasp for breath.

I get by. I do Wordle. I guess TIRED and WEIRD and YEARN.

And the consumerist culture here is apeshitbatshit crazy. That’s not fair to apes and bats. This is on that other species. I will tell you what happened. I go to a café, I go to get coffee. I find this.

IT’S A BEER CALLED JUNIOR ASTRONAUT JUICE.

Every event on Boulder Arts Calendar lures you with drink, art class ‘with a paint brush in one hand and a glass of wine in the other’. ‘Come get a free rain barrel and a free pint’, and ten more listings like it. Our new house comes with a pioneer bar, liqueurs left in it, with a nonchalance, like the floor polish left under the sink. Dennis did take the cash register. I am trying to get rid of the bar. The Sunshine community wants it for the historic one-room schoolhouse down the road. Of course they do.

On my journey to fall in love with a new landscape, I think I have pretty much nailed ZERO.

Luckily, I get to start over every day. Dawn, again. A theatre of colour. It’s all the gels, and all the lighting cues of my whole career every morning.

I remember when we were teching NiX, theatre of snow and ice, and my first kid was 3 months old, and he’s in a snowsuit and I’m in a snowsuit and I’m trying to nurse him through five layers of Gortex and our LX designer Bill says, ‘how was the level, Kendra?’ but I was trying to get the latch – I missed it. Again. And there, in -18C, he doesn’t even shrug, he just calls the cue by number and then ‘standby’ and then, once more,

‘Go’.

Remembering that, I have second thoughts about the species. My therapist says, ‘Kendra, you would be foolish to trust the species, but you can trust individuals.’ And you, Animal, brought me into the company of such good ones.

I learn flowers one by one, Snow-on-the-Prarie, Dotted Gayfeather, Tall Tumblemustard, Giant Woollystar, Wyoming Paintbrush.

I see tiny alpine versions of plants from home, Oregon Grape, Dwarf Fireweed, a Tartarian Maple. When I find them on my land here, I move them into beds closer to home.

Did you catch that? It happened. I say ‘home’ meaning here. I’m guilty. I’ve lied to the jury. Lock me up for seven years.

Ahem.

At home, before I left, I find Common Self-heal, or Heart-of-the-Earth, on the side of Joe Road. Where my old house is. I nearly named my second child ‘Joseph Road’. Here, my road is County Road 83. Which is not a name for a thing you love.

In the end I named my second son the old celtic word for ‘from a beloved land’. But, anyway, that kid changed his name when he was four, to a character from Paw Patrol. He actually gave me two choices, one of which was ‘Lil’ Hooty’. As far away from his birth name as one can go, but then you can’t force someone to love a land.

Here I walk early, because it’s hot. After a few weeks of doing this, I know the names of all the plants along the way, and some of the birds, a few of the stones. I walk to the compost and the grasshoppers leap aside with a clacking sound. A clapping sound. I cross upstage left. I make theatre for grasshoppers.

My new driveway used to be the main street of the town of Sunshine during the Gold Rush. Dennis, who lived on this land for 60 years, told me that. He has hands that have built a house, so, when he points his hand, it makes something solid. He points, ‘the jail was here and the general store across, and next to it, where you sold the gold, and down there was the hotel, you see.’ I see. In order to make a claim you had to dig a hole ten feet down. Hand-dug holes in grey granite and white quartz. The land has five of these. Some are now full of wildflowers, some full of burnt wood, these hand-dug holes. Are they really dug when you are boring through rock? These things are not dug as much as they are broken.

On the bottom of the property there is a decommissioned commercial gold mine. Instead of filling it in, they put a sturdy gate with bars, so the bats can live there. Brandon from across the street asks if I have the key. At the backside of the gate, apparently, there is a lock, and you can open the mine and go inside. If you were here, Animal, we would do that. Taking theatre where it has never been before! As yet, I have not tried the key. It is not that I am not curious about the gaping hole here– it’s just a little much metaphorically…

I play Antje Duvekot on Spotify so I can sing the line, I am teaching myself to be brave.

One morning, I bump into Chris, Mayor of Sunshine, on County Road 83. Because I’ve been playing DnD with the kids, I can tell you he is a halfling. He walks with a staff and doesn’t have to bend over to look in the mailbox. It’s 7am and the mail came 18 hours ago, which he knows I know. He lets the mail sit overnight to kill the virus.

We talk about wild turkeys, which he feeds in his backyard, along with the deer and fawns. But mostly he wants to talk about the lion.

Chris doesn’t hunt but he will go out at night with his pistol if he hears a scream. One night, in winter, it was a coyote bleeding out. Blood in the snow. The lion nearby in the meadow. ”I says to the coyot, who was crying, ‘this is not my business’ and went home, put the pistol on the table and had a double shot myself.”

The conservation officer arrived months later, and knew about the strike. The lion has a collar, you see, and it’s tracked. The conservation officer found the kill site, but Chris got the coyote’s skull. A lion tooth-hole bored straight into it at the top. It hangs in the Mayor’s backyard.

Then, the Mayor points to the gulch below my house and says that’s where the lion lives, but not to worry about the bear. Ally warns me that if I put watermelon rinds in the compost that the bear will come and then will hang around for 5 years. Dennis tells me that the bear will come on the full moon, so lock your car. The real estate agent told me a bear broke into her car to get her chapstick. I grip my chapstick.

The Mayor promotes the lion; it was here before any of us. The conservation officer will not be taking it away. My cats shuck their collars in 20 minutes, but that lion wears his. Promotion is a big part of staying alive. I can say that now with some authority. Someone is tracking the lion, but I am a little lost. When baristas ask my name to write it on the cup, I draw a blank.

Halfling or human, or coyot’ or housecat, we are tender and soft-bellied and we live with lions. We will be torn open at any time. Holes in the hardpan, the granite, the skull of a coyote. The thunderstorms come every day and the rain slams the ground, throwing rocks into the road. But, along with the hardness, everywhere, all the time there are the flowers. Eleanor, walking her dog, calls it a ‘superbloom’. I walk in the mountains the next morning and the next. The line of the mountains is like handwriting, and I squint to make out what it says.

And I work on transforming the huge gravel driveway into garden space. I move things around that are on the property. I have 100 unanswered emails, but can’t stop the lugging of flagstone, the making of path. I meet with someone from a Local Theatre Company. They do The Well-Made American Play. The Artistic Director tells me that the company produced one of his own shows, a sort of Christmas thing, and then it got picked up by a cruise line and he got to go on a Virgin Cruise. This may be the moment when I got pregnant with aliens. I drive back up the mountain and lug a few pieces of flagstone into place.

The house that Dennis grew up in was not built in the same place as our new house. It was actually built around the old stone jail. Five kids in that family. I imagine being that mom with five kids very close together in age, with her very own jail in the basement. That’s Gold. Dennis’ family had a bar in the house as well, and when the fire came, the liquor bottles exploded throwing chartreuse and lilac and ice blue bottle pieces far into the brush where the bulldozers couldn’t get. I need to find a job, but instead I walk the land and collect as many broken shards as my hands can hold.

Ah, but I forgot to tell you, Dennis’ family home burnt down in the Sunshine Fire of 2010. It came on quick, as the wind was carrying it, and folks only had 2 hours to evacuate. 126 houses in this tiny town burned. 13 years ago is this town’s yesterday. Folks introduce themselves to me with a description of what they lost.

One night, I find a fox waiting by my door. Dennis says to throw him half a hotdog. Dan, who lives uphill, gives him eggs. We don’t feed him, because we think he might gnaw on our cats. The birds empty a bird feeder in three days. The jays scream about it. I enjoy the feedback.

Dennis tells me that things grow well where the old outhouses were, so I look for fecundity. I go to the native plant nursery in town, looking for stuff to plant in the new driveway beds, and can’t afford anything. I come back and walk around the property saying to myself, ‘well, now, here’s a Tartarian Maple for $115 dollars off.’

And the heat is incredible. It’s in the 90s day after day. I don’t know the conversion exactly but best guess is 110C — I mean, it is beyond boiling. In our DnD game, we fight a Fire Salamander. My character, Grog, is knocked unconscious, despite the fact that he wields a maul and has a strength modifier of 3. The game ends at 8 and I’m asleep by 8:10. Sleep will restore my hit points.

In the early morning, I steal another hour to move the flagstone. When I lift the stones, I sometimes find a couple of dull-black beetle who scuttle about. And you know me, I’ve never been a lover of insects. At home, if I saw a spider I would put a dish towel over it and throw the whole bundle outside. That towel might stay outside for days. But, here, I’m glad to see beetle. I watch them as long as I can. I realize: I’m lonely.

I call Colin to complain, but he is busy.

The old men in Sunshine are kind. One brings me four zucchini. One has a dog named Phoebe. We talk about the winter. Dennis gives me his old chicken tractor. In the spring, get a dozen eggs and an incubator. He tells me that he kept the chicken tractor outside the bedroom window. Dennis really loves animals.

Myself, I am preparing our house for an axolotl. They are illegal to own as pets in Canada, but in the land of Junior Astronaut Juice you can find them at the local pet store. My kids are cycling the water, and I’m getting a worm farm to feed the axolotl, who can live for 15 years and needs the water temperature to be between 60 and 68 degrees F. I don’t know the exact conversion but that is approximately impossible, just so you know the score.

I’d like to get my kid a more suitable pet, a five-pound therapy dog, like the one his caregiver at home had. I look up the breed, Russian Toy Terrier. There is an 8-week-old puppy for 1000 bucks in Pennsylvania. This puppy is so wee, it would fit in the palm of your hand even if you were already holding Junior Astronaut Juice. My eldest wants a Colorado Mountain Dog, which is basically a small horse. A friend sends me an IG post about house cows. The sofa is white, so maybe not in the family room. If we are counting worms and axolotl and dogs and lions and bluejays and a dozen eggs and an incubator, a house cow, and beetle under flagstone and grasshoppers under foot, I mean, that’s a lot of animal. But, you know, it doesn’t fill the Animal-sized hole in my heart.

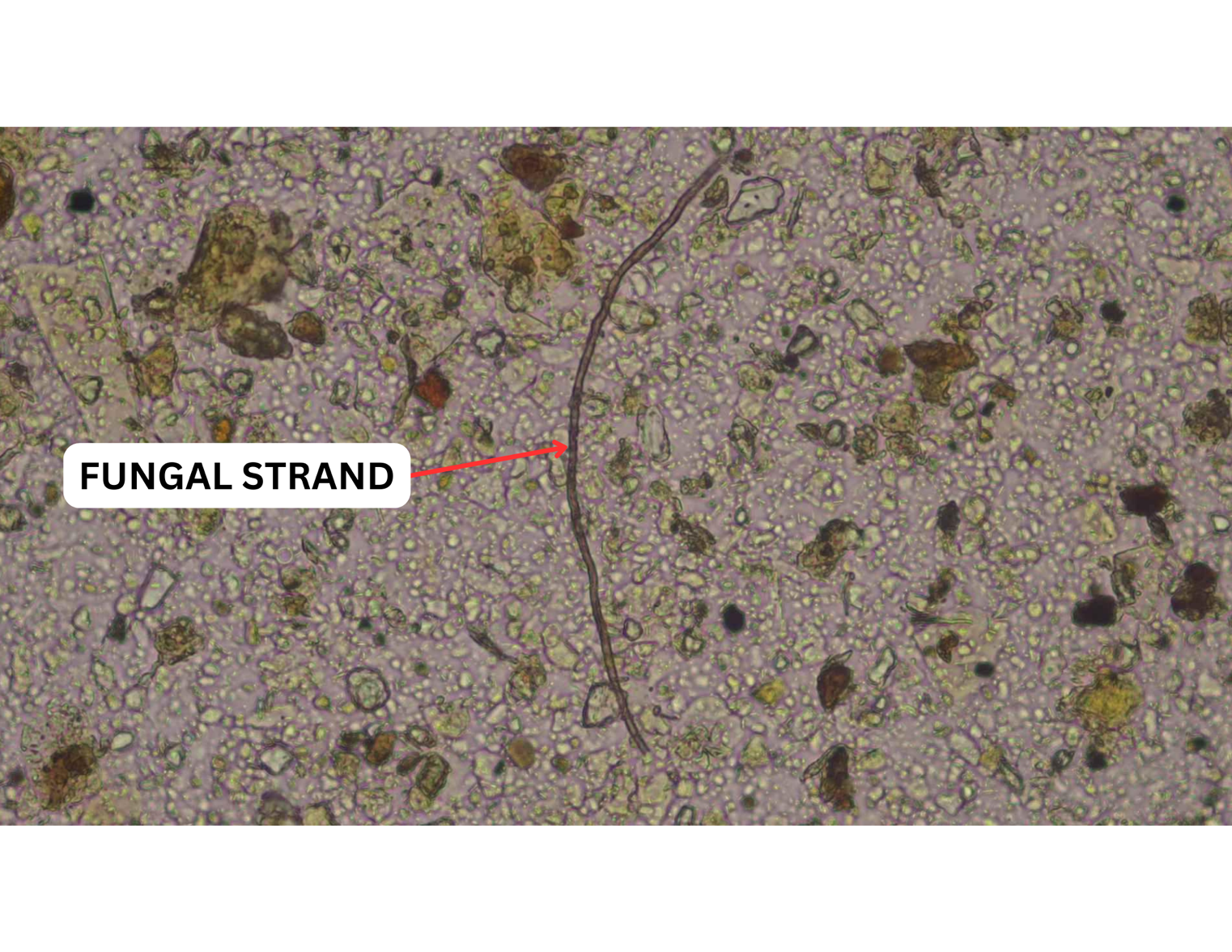

My nephew in North Carolina is a budding farmer, and I send him a Ziploc bag of dirt. The wildfire burned hot and killed the microbial life of the soil. Yet, there is this: he sends back a photo of a few fungal strands. I look at them every day.

I pick up pinches of dirt wherever I go and feed the compost pile the microbes. My nephew tells me to do this anywhere I see local plants thriving. I bring my attention to thriving. I break down cardboard moving boxes and lay them on the hill to begin a garden. Dennis gives me some metal stakes for a garden fence and says I can borrow a pounder to knock them in. Dan says he doesn’t fence his veggie garden, says there is enough for the deer too. 811 has some wild roses.

I start a compost pile, but it’s too dry to break down. I yearn for moisture myself, and it cannot be found. The cats stick their heads in my water glasses. Shower steam evaporates instantly. I feel stubborn about it. I stand in the shower like a raincloud and cry. But then I turn off the shower and pack the lunches. I think of the line in The Magic Hour, ‘Life reaches, as it is wont to do, both up and down at once.”

I’m thinking about you, Animal, again and Barbara. How is it today, I wonder and check the weather app. The chanties should be up, on the moss bank by the B&K, after eight days of rain. There aren’t many things so golden, and Barbara is so attuned to colour that she is sure to find one, or five, or fill her basket. Lobster mushrooms can go until November. Check at the base of sword ferns. Show her the slow movement from the forest floor. It is almost like water coming to a rolling boil-long before the mushrooms break the surface, something is moving there. That is the real magic, walking and feeling everything coming. If she picks something, have her carry it loose as she walks. Each mushroom has a million spores. Over the years, she will begin to see the trail of her past through the woods where she walks. Where she takes you. Your new caretaker, Animal.

Colin and I talked a year ago, when I saw the writing on the wall, and knew I would have to leave. Should we put The Only Animal down? No, we thought, we decided we would try. There is a sort of dry talk in the sector about succession planning, and lifecycle of an organization and all that. It’s not dry in practice. It’s more like artistic blood transfusion. It’s CPR. It’s intimate and uncomfortable.

You are becoming something new. You enormous 18-year-old beast. You warm-hearted Mammoth. You make a great companion.

For me, here, in the past week or so, out here on a rocky mountain, I have been beginning to see theatre. It’s pointless, there is no funding for individual artists, and I will never make a big show again, but I see it. In the empty foundations of the burnt-out buildings on the hills. A show called Wildfire. A show called Gold. Shows in the mines. I see theatre of rock — rock sets, rock props. Theatre in mailboxes. Beetle and grasshopper for actors. An intimate chicken theatre. Maybe attended by a temperature-sensitive aquatic salamander, very small dog and a house cow. I gather all the possibility inside me. This is where the theatre really is: in possibility.

Most of all I think about the show in the Wind. It blows and blows and blows. It eats mountains. It throws the rain through the window screen so hard you get puddles by the couch. It bangs doors and scares the cats. I always wanted to make a show that you watch lying on your back. Here the clouds move so quickly in the wind, it is almost like cartoons. Could you improvise with them? Could musicians lie on their backs and play that song? Could you narrate that animation in real time? Would the swallows be dependable as dancers? Would the Bluejay scream? Could I finally use the 20 helium balloons left over from Other Freds?

As I write this, the clouds are pink with sunset. They are not whipping by tonight, instead, still. It is a denouement of sorts. I will walk after dinner. And go to bed early. I’ve been saving the Star show for winter, because at this point, I don’t want to miss the dawn. I don’t need to set my alarm, I am woken by the theatrical potential, unmissable, even in that darkest hour. I whisper, ‘go’.

Yours, ever so,

Kendra